Competence Levels for Deepening TRRACCK in Relationships with Indigenous Nations and Individuals

One of the guiding shared inquiries of the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (GTDF) Collective has been the question of how we can develop the intellectual, affective and relational maturity that we need to collectively face complex social and ecological challenges. Specifically, much of this inquiry has focused on identifying the work that settlers need to do to show up to their relationships with Indigenous Peoples differently – in ways that can begin to interrupt the usual colonial patterns of extractive, transactional, and paternalistic relations.

Led by GTDF member Cash Ahenakew, Cree scholar of education and CRC in Indigenous Peoples’ Well-Being, and guided by GTDF’s long-time collaborators in the Teia das 5 Curas Indigenous Network, through this inquiry, we have created numerous pedagogical exercises and experiments that invite others and ourselves to identify and begin dismantling the barriers to weaving good relations between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Peoples, particularly in settler-colonial spaces, like what is currently known as Canada and Brazil.

This includes Cash’s book, Towards Scarring the Collective Soul Wound, the book Towards Braiding led by curator Elwood Jimmy, the poems “Wanna be an ally?”, “Why I can’t hold space for you”, and “Beyond ‘thank you for the real estate’,” the exercise “Returning Lands”, the workbooks “Developing Stamina for Decolonizing Higher Education” and “Beyond Window-Dressing Reconciliation in Healthcare,” and Cash’s text, “Towards accountable relations and relationship building with Indigenous communities.”

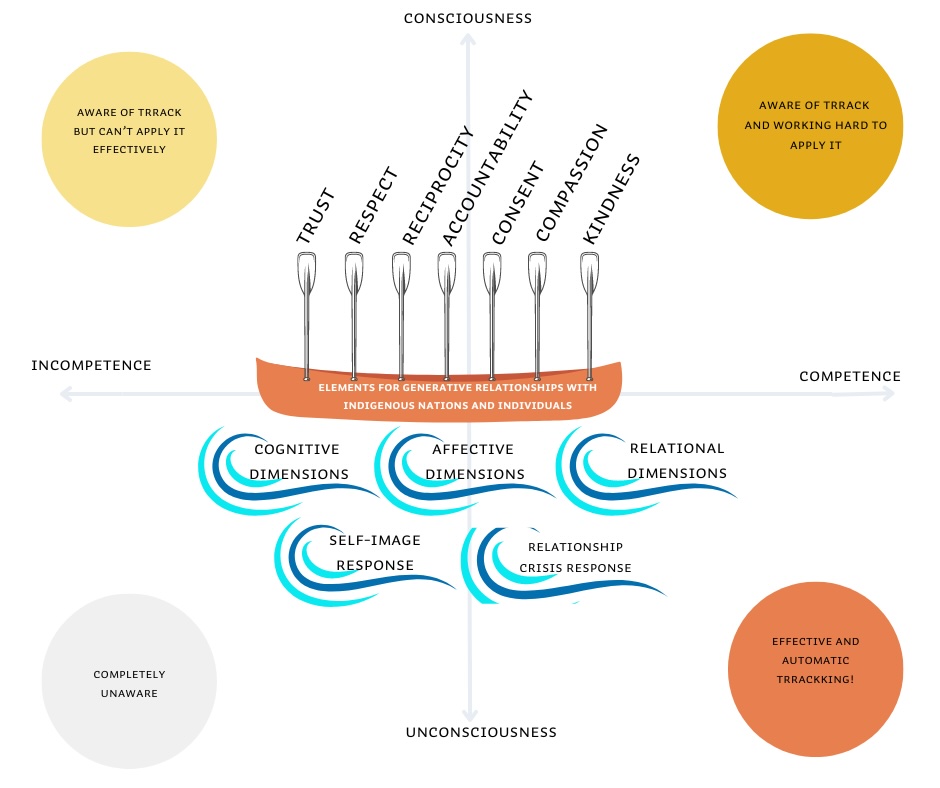

In addition to creating our own materials, GTDF has engaged with other collectives, scholars, and knowledge holders around these issues. We were particularly grateful to encounter the work of Potawatomi philosopher Kyle Whyte, who summarized the necessary conditions for good relations: trust, respect, reciprocity, accountability, and consent. We have adopted the acronym “TRRAC” to quickly summarize these relational qualities. Recently, in response to the weight of complexity and pain carried by youth, Blackfoot scholar and Indigenous language advocate Sandra Manyfeathers has requested that we add compassion and kindness to the list, making it TRRACCK or TR2AC2K.

Throughout our inquiry, we have learned that many barriers to TRRACCK are unconscious. Non-Indigenous peoples in settler colonial spaces in particular have been socialized to reproduce relational patterns that affirm their authority, autonomy, accumulated wealth, benevolence, good intentions, contributions and self-image. In the context of a settler colonial system and its institutions, settlers are neurochemically wired to desire and demand these things – and thus, they often become dysregulated if these things are challenged or denied. This means it is not enough for settlers to be intellectually aware of the harms of colonialism or the imperative to foster ethical relations. They must make a continuous effort to interrupt and unlearn unconscious colonial habits and rewire the unconscious. This requires working not just with cognitive but also affective and relational dimensions of the self.

Because non-Indigenous people are inclined to overestimate their capacity to build good relations with Indigenous Peoples and underestimate the difficulty and complexity of doing so, sometimes it is only in moments of relational crisis that they can accurately assess where they are “really at” in this un/learning process, as these moments “test” one’s cognitive, affective, and relational capacities for TRRACCK.

Although we are suspicious of the Western conceptualization of “competence”, we created the following “cheat sheet” using Noel Burch’s 4 stages of competence model. The cheat sheet was designed to help remind non-Indigenous Peoples in settler-colonial contexts of the cognitive, affective, and relational capacities that are necessary for deepening TRRACCK in relations with Indigenous Nations and Individuals. If this is your positionality, you can use this framework to engage in honest and hyper-self-reflexive assessments about your current capacities and the work that you still need to do toward deepening TRAACCK.

TRRACCK Cheat Sheet

TRRACCK stands for Trust, Respect, Reciprocity, Consent, Compassion, Accountability, and Kindness. These elements are essential for building and maintaining generative relationships with Indigenous Nations and individuals.

Trust involves fostering a sense of reliability in your actions and words. It requires consistency and transparency in your interactions, demonstrating that you are dependable and have the best interests of Indigenous communities at heart.

Respect is about honoring the inherent dignity and worth of Indigenous individuals and their cultures. This means actively listening (especially when it is challenging), valuing their perspectives, and avoiding actions or words that diminish their experiences and knowledge.

Reciprocity is the practice of mutuality. In relationships with Indigenous peoples, it means acknowledging the gifts of time and labour of Indigenous individuals and communities, especially when they are trying to teach you. It also involves giving back in meaningful ways that are valued by the community.

Consent is crucial in ensuring that Indigenous peoples have control over what happens to their lands, cultures, knowledges, and bodies. This means seeking permission, respecting their decisions, and recognizing their sovereignty and autonomy.

Compassion involves showing genuine care and concern for the well-being of Indigenous individuals, Indigenous communities and Indigenous Lands. It means being empathetic, connecting with the pain, anger, and struggles under colonialism, and offering support in a genuine and meaningful way.

Accountability requires facing responsibility for your actions and their impact on Indigenous communities. It involves being honest about mistakes, seeking to repair relationships, and being committed to ongoing learning and unlearning.

Kindness is the practice of treating others with warmth and generosity. It means acting with gentleness and care, fostering an environment where Indigenous individuals feel valued and respected.

Read the trracck cheat-sheet and reflect on your perceived and actual competence levels. Remember that the actual competence level will only surface when you are deeply challenged and close to the “edge” (in a crisis)

Unconscious Incompetence (unaware of TRRACCK or how to perform it)

Cognitive Dimensions: Lack of awareness or understanding of TRRACCK practices; believes current understandings are sufficient.

Affective Dimensions: Indifference or lack of emotional engagement with Indigenous perspectives.

Relational Dimensions: Interactions are superficial, tokenistic, or paternalistic.

Response to Challenged Self-Image: Defensive; denies or dismisses challenges, may feel victimized or misunderstood.

Response to Relationship Crisis: Blames the other party, disengages, or avoids addressing underlying issues.

Conscious Incompetence (aware of TRRACCK but cannot perform it consistently)

Cognitive Dimensions: Aware of TRRACCK but struggles to apply them; recognizes gaps in knowledge and skills.

Affective Dimensions: Feelings of discomfort, guilt, or overwhelm when confronted with challenging Indigenous perspectives, insecurity creates undo labour for Indigenous individuals and communities

Relational Dimensions: Attempts to build relationships but is constantly seeking validation, which places a transactional unfair burden on Indigenous individuals and communities; often makes serious missteps; acknowledges limitations.

Response to Challenged Self-Image: Experiences shame or frustration; may withdraw or seek out self-actualization.

Response to Relationship Crisis: Seeks external validation or guidance; seems open to feedback but struggles to implement changes effectively due to struggle to understand or accept it.

Conscious Competence (effort needed to perform TRRACCK consistently)

Cognitive Dimensions: Understands TRRACCK and actively seeks to apply it in interactions.

Affective Dimensions: Emotionally invested in fostering respectful and reciprocal relationships, with occasional romanticization, idealization and projection; less invested in being validated as a good ally

Relational Dimensions: Builds meaningful, though sometimes problematic, relationships with Indigenous individuals and communities.

Response to Challenged Self-Image: Reflective; engages in self-inquiry and seeks and is grateful for constructive feedback.

Response to Relationship Crisis: Engages in open dialogue, acknowledges mistakes, and works collaboratively towards resolution.

Unconscious Competence (automatic TRRACCK)

Cognitive Dimensions: Integrates TRRACCK seamlessly into all aspects of relationships and interactions.

Affective Dimensions: Feels a deep, intuitive connection and respect for Indigenous perspectives without romanticizations, projections and idealizations, and without seeking validation; understands perspectives that denote anger, frustration, resentment and pain, and can hold space for the complexities of Indigenous communities and individuals as well as one’s own complexity

Relational Dimensions: Consistently nurtures relationships based on mutual respect, reciprocity, accountability, consent, compassion and kindness beyond engagements with Indigenous peoples.

Response to Challenged Self-Image: Maintains humility; welcomes challenges as opportunities for growth and learning.

Response to Relationship Crisis: Responds with empathy, resonance, flexibility, and a commitment to restorative practices.

Image provided by Val Cortes

Explanations of Dimensions and Responses

Cognitive Dimensions: This involves awareness and understanding of TRRACCK as an intellectual practice, knowledge of Indigenous histories and perspectives, and the ability to critically reflect on one’s own biases and assumptions. Ability to “track” the movement of ideas/social constructs: where they come from, how they land, their ripple implications, how they interact with conflicting and converging ideas.

Affective Dimensions: These dimensions encompass the emotional responses and attitudes towards Indigenous perspectives, including empathy, emotional resilience, and the ability to manage feelings of discomfort, shame or guilt. Ability to track the movement of affective states and desires both within and around oneself and to track origins and impacts of affective states.

Relational Dimensions: These involve the quality and depth of relationships with Indigenous individuals and communities, including meaningful and reciprocal interactions and the quality of relationships in general. Ability to track the movement of connections and disconnections.

Response to Challenged Self-Image: This outlines how individuals react when their self-concept or identity is questioned, progressing from defensiveness to reflection and growth.

Response to Relationship Crisis: This describes the approach individuals take during significant relationship challenges, from avoidance and blame to open communication and collaborative problem-solving.

Caution – The Drunning-Kruger Effect: The Dunning-Kruger effect is a type of cognitive bias in which individuals with limited knowledge and experience in a particular area tend to overestimate their own skills and abilities. This phenomenon was first identified by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who observed that novices often lack the critical self-awareness necessary to accurately assess their own competence. Their limited understanding leads them to miss the complexities and the full scope of what they do not know, resulting in a belief the hat they are more skilled than they truly are. This initial overconfidence has been colloquially described as “climbing Mount Stupid.”

As these individuals begin to encounter obstacles, make mistakes, and receive critical feedback, their overconfidence is confronted, leading to a significant shift in self-perception. This phase often involves intense frustration and a loss of self-efficacy, where people might grapple with feelings of shame and disillusionment, or alternatively, deflect blame onto external factors. This challenging period is sometimes referred to as the “fall from Mount Stupid.”

With greater knowledge comes a deeper appreciation of the complexities and conundrums involved, which helps individuals understand just how challenging the field can be. This increased awareness can help people develop a more accurate, and typically more modest, self-assessment of their abilities, which then produces the conditions for people to show up with much more openness and humility.

Over time, as individuals acquire expertise, their evaluations of their own competence become more aligned with reality. They become adept at recognizing their limitations and understanding their true level of skill. This journey from overconfidence to a more grounded and humble self-perception encapsulates the essence of the Dunning-Kruger effect: initially, beginners often display overconfidence, while those with more experience develop a clearer, more realistic view of the limits of their own expertise, which is not overly sensitive to negative feedback. This model is useful as a self-reflective tool to understand and navigate the emotional rollercoaster of becoming proficient in complex and challenging areas like TRRACCK. It helps normalize the feelings of doubt and frustration that come with advanced studies, while also emphasizing the importance of perseverance, openness to continued learning and humility.

Note: TRRACCK encourages us to see ourselves and others as complex and contradictory, not as coherent, self-interested subjects shaped by modern/colonial systems. We must question narratives that impose simplicity on complexity and acknowledge our unconscious aspects.

Engaging with the unconscious involves questioning our desires and stepping back from ego-driven motivations. We shouldn’t insist others see us as we see ourselves, understanding that views are shaped by social and historical contexts.

People who are unconsciously competent at TRRACCK see it as a lifelong journey requiring a truckload of genuine humility. Genuine TRRACCK is recognized by others; those who claim competency or seek validation are likely doing harm. Practicing TRRACCK non-transactionally means offering kindness and generosity without expecting recognition, acknowledging our role in a wider living network. see also “Towards Eldering“.

Invitation: Reflect honestly on your competence levels for TRRACCK. How could building TRRACCK unconscious competence improve all relations in your life?